Since launching in 2018, the program to help Black youth has helped hundreds of them find work as first responders. But funding remains a problem.

Lieutenant Quention Curtis exits Engine Co. 21, the first Black fire company founded in 1872, at the Black Fire Brigade in Washington Park on Dec. 28, 2021.

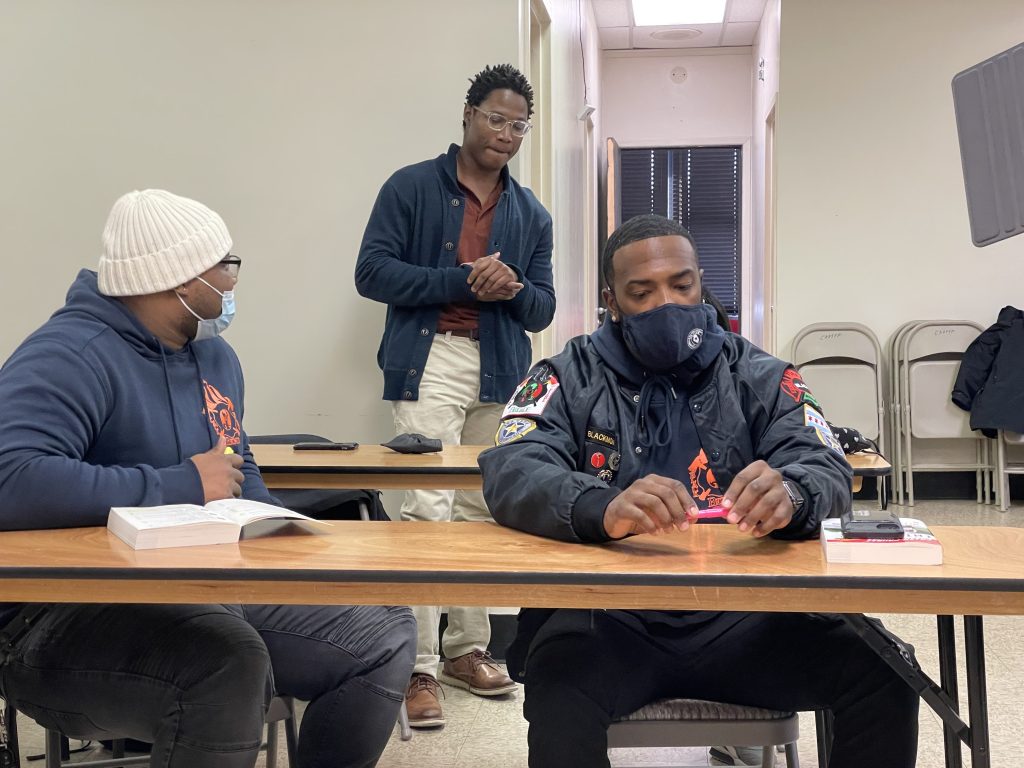

WASHINGTON PARK — Three times a week, about a dozen students walk through the doors of the Chicago African American Firefighters Museum, passing images of heroes from the past as they chart their futures.

The decommissioned Washington Park firehouse and museum, 5349 S. Wabash Ave., also is home base to the Chicago Fire Brigade, a nonprofit organization where Lt. Quention Curtis — known as “Lieutenant Q†to his students — trains young adults to become first responders, preparing them for emergency medical technician tests or firefighter exams.

Since the program launched in 2018, 440 students have gotten jobs in the industry, said Curtis, a 34-year veteran of the Fire Department.

For Curtis, the mission is twofold: He wants to give young people a sense of purpose and add much-needed diversity to the Fire Department’s rank and file. That’s also an issue Fire Commissioner Annette Nance-Holt, the first Black woman in that role, vowed to address with the introduction of a new exam that would get more women and people of color through the door.

But Curtis said getting buy-in from local leaders to ensure there is opportunity and upward mobility for people of color within the Fire Department remains an uphill battle.

“I’m a former police officer, so I’ve seen my share of everything. I hear people talk about crime, but they don’t do anything,†Curtis said. “If you teach a kid to save a life, they’re going to be less likely to take one. You stop the bullets by adding opportunities. Without opportunities, there’s nothing you can do.â€

‘You Can’t Really Want Change If You’re Not Actively Pursuing It’

Curtis’ program accepts applicants ages 18-30 who reach out via the Black Fire Brigade website. From there, they’re placed on a waiting list until their number comes up. Trainees go through a criminal background check; in certain cases, the organization’s staff helps with record expungement. They also help applicants secure driver’s licenses and get driving privileges reinstated.

The program uses the same training modules employed by fire departments across the country. Once students complete both phases of the program — which runs 90-120 days, depending on the field of study — they earn the certifications required to enter any first responder agency of their choice.

The program connects people to opportunities and provides resources to help them navigate a complicated system that often keeps out young hopefuls, Curtis said.

Lieutenant Quention looks over EMS equipment at the Black Fire Brigade in Washington Park on Dec. 28, 2021.

That help was invaluable to Robert Hamilton, an Army veteran training to become a firefighter. After applying to the Maywood Fire Department, Hamilton was asked to take a polygraph but didn’t receive a letter about it until weeks after the deadline. With Curtis’ help, Hamilton was able to take the polygraph and get a slot to take the firefighter’s exam, which he passed.

Hamilton, an Englewood High School alumnus, is part of the brigade’s current cohort and hopes to return to help others after he graduates.

“You can’t really want change if you’re not actively pursuing it. This program is doing that. It’s offering countless opportunities and opening doors for minorities,†Hamilton said.

Dakota Burnett was working at Mariano’s when a fireman told him about the Black Fire Brigade. He’d enrolled in EMT courses at Malcolm X College but was having trouble paying the tuition before the deadline. The chance meeting with the fireman was a sign, Burnett said, and he started the program Sept. 1.

“He told me that the brigade had already set a path for me to get through this thing free, that it was already established for me to succeed,†Burnett said. “To go from worrying about tuition to being able to start the program for free the very next day? That’s nothing but God, and I’m grateful.â€

Burnett passed his EMT exam in early December. He now works for a Lifeline, a private ambulance company.

‘Every Bit Of Progress We’ve Made, We Had To Sue To Get’

Curtis, a Cabrini Green native, knows the value of opportunity for young Black people.

It wasn’t until Curtis, then 12, saw a Black fireman step off a truck that he realized he, too, could be a hero, he said. He graduated from Near North Career Metropolitan High School, then worked as a city laborer as he waited to hear back from the police academy. He got the call in 1987, working on the force for a year before landing his dream job with the Fire Department.

Curtis’ first few years on the job were difficult because he’d landed a plum assignment usually given to children of battalion chiefs, which made him persona non grata, he said.

“I caught hate from all sides. A lot of people believed I wasn’t supposed to be there,†Curtis said. “The chiefs’ kids didn’t like that I wasn’t one of them, and the Black firemen who’d been rejected after requesting the detail didn’t understand how I got it. I had to prove myself, so I worked hard, and over time they had no choice but to respect me.â€

Lieutenant Quention Curtis inspects Engine Co. 21 at the Black Fire Brigade in Washington Park on Dec. 28, 2021.

Curtis found success, and his two sons have followed in his footsteps to become firefighters. But the department has repeatedly stalled in meaningfully diversifying its ranks, he said.

The department of around 5,000 firefighters, medical responders and support staff is about 64 percent white and 90 percent male.

Holt and her predecessor have said there has not been a firefighters entrance exam since 2014, meaning the department is hiring from the same seven-year-old list of candidates. An entrance exam is planned for early 2022.

Even without a new recruit list, Curtis questions the department’s hiring practices. Data Curtis obtained from a Freedom of Information Act and reviewed by Block Club showed 54 percent of firefighters and 67 percent of paramedics hired from 2015 to 2020 are white.

More broadly, the department long has been dogged by allegations of sexism, sexual harassment and racism. A Better Government Association investigation found the city spent $92 million paying out racial and gender discrimination lawsuits against the department between 2008 and 2017.

Last year, the city paid $1.83 million to female firefighters who accused department leaders of protecting serial sexual abusers. A city watchdog also determined last year the department’s rules were “insufficient†to prevent discrimination.

Thousands of Black prospective firefighters sued the city in 1998, alleging officials unfairly excluded minority candidates who’d passed a 1995 exam but were not hired. After a Supreme Court ruling in 2010, a federal court order the following year forced the city to pay $30 million to those who were denied jobs. The department also had to hire 111 Black firefighters who’d passed the exam 16 years earlier, and the city was required to pay their back pensions.

“Every bit of progress we’ve made, we had to sue to get,†Curtis said.

Curtis said it’s not enough to have Nance-Holt and other Black firefighters holding key leadership positions — there needs to be diversity throughout the agency.

“We have too much window dressing. People believe that because there are Black people in higher positions, there isn’t a problem,†he said.

The Fire Department did not respond to requests for comment.

Despite accolades from city and state officials — Mayor Lori Lightfoot made an appearance at a recent Black Fire Brigade event — Curtis has relied on donations to keep the organization going. He often pays out of pocket for textbooks, tuition and other necessities, particularly for students who need housing, he said.

City and state funding — and financial support from the Fire Department — would allow Curtis to get more young people into the program and help public safety efforts, he said.

“We’ve been turned down for so many grants because they say we don’t qualify,†Curtis said.

The timing couldn’t be better for the city to invest in training a new generation of Black first responders and righting the wrongs of the past, Curtis said.

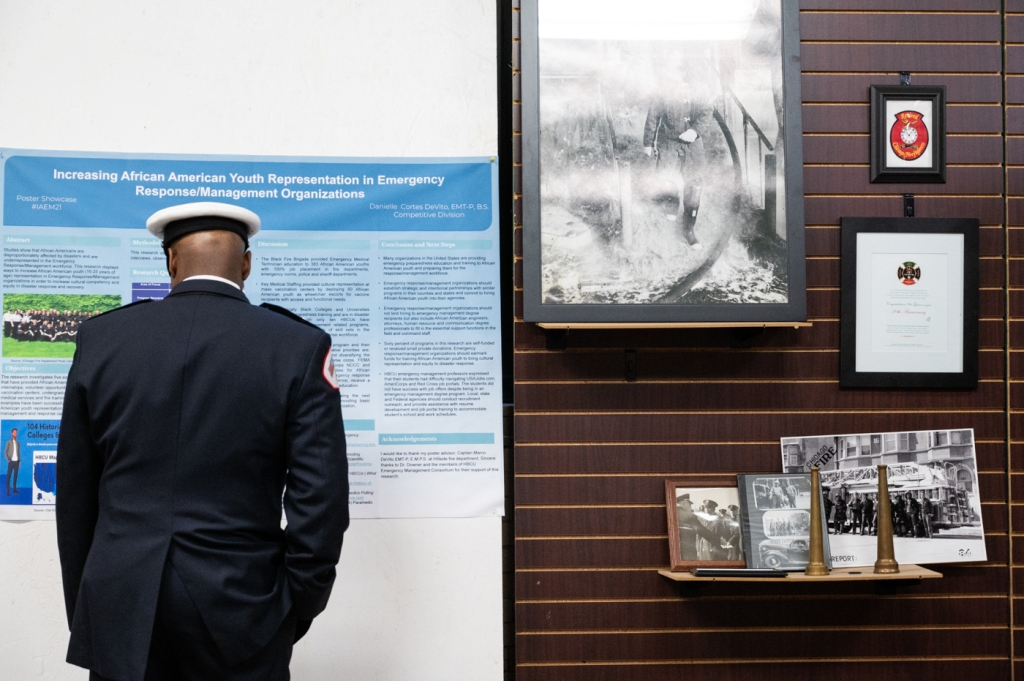

December marked the 150th anniversary of Chicago’s first Black fire company, Engine 21, a team of six known for introducing the trademark pole that became commonplace in firehouses worldwide. But for all their innovation and hard work, the company still had to fight to be seen as equals, even petitioning city officials to appoint Engine 21’s first Black captain.

The contributions of the city’s first all-Black battalion have been obscured, which has motivated Curtis to keep fighting a system that still treats him as an unwelcome guest, he said.

Even if outside support doesn’t grow, Curtis is determined to continue his work.

“We’ve taught them life safety skills that they can use at any time, at any moment to save anybody’s life,†Curtis said. “That is the difference between our program and others out there. This program needs to be funded because it is the No. 1 crime prevention program in the state of Illinois, bar none.

“We’ve taught them to fish, and they’re going to eat forever.â€

Lieutenant Quention Curtis poses for a photo next to Engine Co. 21, the first Black fire company founded in 1872, at the Black Fire Brigade in Washington Park on Dec. 28, 2021.

Subscribe to Block Club Chicago, an independent, 501(c)(3), journalist-run newsroom. Every dime we make funds reporting from Chicago’s neighborhoods.

Click here to support Block Club with a tax-deductible donation.

Listen to “It’s All Good: A Block Club Chicago Podcast†here: